InTune with Cents

Many choirs are typically on hiatus during the summer. Below are some choral concerts taking place in July and August.

The Elora Festival, built around the Elora Festival Singers, is always a rich source of choral music in the summer. Taking place July 13 to August 5, choral highlights include Mendelssohn’s Elijah, Britten’s rare 1937 opera composed for radio performance, The Company of Heaven, Paul Halley’s celebrated Missa Gaia, and a concert devoted to the music of American composer Eric Whitacre.

The Elora Festival, built around the Elora Festival Singers, is always a rich source of choral music in the summer. Taking place July 13 to August 5, choral highlights include Mendelssohn’s Elijah, Britten’s rare 1937 opera composed for radio performance, The Company of Heaven, Paul Halley’s celebrated Missa Gaia, and a concert devoted to the music of American composer Eric Whitacre.

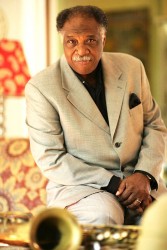

The Nathaniel Dett Chorale performs at the Westben Arts Festival Theatre — the Barn — on July 15.

The Toronto Jewish Folk Choir sings at the Ashkenaz Festival, which takes place August 28 to September 3.

The Ontario Youth Choir, a group that has fostered excellent singers over many years, performs in Kingston on August 24 and in Toronto, August 26.

The Ontario Youth Choir, a group that has fostered excellent singers over many years, performs in Kingston on August 24 and in Toronto, August 26.

In May, I wrote about a colleague who passed away suddenly, and about the bonds, loyalties and joys of singing that draw the choral community together. This month, I address an aspect of choirs that can be awkward, contentious, even divisive —the issue of singing choral music for money.

As a young singer who fell in love with choral music, I was in awe of the musicians who were part of professional choral ensembles. To get paid to do something that was so much fun seemed astonishing to me. When I began singing for these groups myself, I was gratified to be paid, but I quickly learned that this could not be my only source of income, and that I would have to find other work to put food on the table.

Looking back, what I find odd is that this simple truth — choral singing won’t pay the bills, and you will need more than classical vocal training to generate income through music — was never openly discussed, not by singers, conductors, arts administrators or vocal teachers. The subject remains a delicate one. Why is this the case?

Perhaps in a well-meaning attempt to encourage and foster passion for and commitment to the arts, or perhaps because open discussion about money is often considered taboo, musicians avoid informing their students about the often difficult economic realities of a career in music. Myself, I would never have become anything but a musician — the ability to count to four and a vague awareness of pitch are about the only skills that I possess — but being armed with the some hard economic facts about the musician’s life might have led me to make more strategic, or at least more informed, choices.

My own experience has made me stubbornly determined to be open with younger musicians regarding money issues — not to stomp on their dreams, but to help them go into their chosen profession armed with some practical knowledge about the different elements at play.

In the specific case of choral pay, one of the likely reasons for the lack of discussion may be the awkward fact that it lags behind pay for other musicians. The choral ensembles, churches and synagogues in the Southern Ontario region that pay choral singers generally do so at the rate of $20–$30/hr. Most professional ensembles are in the $24–$28/hr range. By contrast, unionized opera choruses pays between $31–$38/hr. The minimum rate of pay for instrumentalists of all kinds, according the Toronto Musicians’ Association, is $42/hr for a minimum two-hour rehearsal call, and $50/hr for a minimum three-hour performance call.

Whether instrumentalists always get this minimum rate is another question entirely. The point for this discussion is that our most accomplished choral ensembles often pay a significant amount less per hour than the minimum rate of pay for an orchestral instrumentalist or unionized opera chorus singer. An experienced choral singer performing a two hours-plus Messiahconcert filled with grueling choruses will get paid half of what the trumpeter and percussionist, fresh out of school, get paid for playing in three or four movements comprising 12 to 14 minutes of music.

Still, is this discrepancy truly a problem? With so many singers ready, willing and eager to sing for free, shouldn’t hired singers be grateful for whatever they can get? There are parts of the world in which the idea of a paid choral singer is unheard of.

My own opinion in this matter — tiresomely obvious to anyone who spends more than ten minutes in my presence — matters less than yours, and anyone else’s involved or interested in choral singing. But since you ask, my belief is that choral singing in Ontario — so accomplished in so many ways — could certainly stand to take a professional leap forward. Why should choral singing not be a skilled and specialized métier, a viable career choice, rather than a very poor second to soloist work?

Open, public discussion of this question might offer some creative solutions. What follows are a few statements and suggestions for dialogue , debate and possible action for those involved in choral training and performance.

Organizations that hire choral singers have a ethical responsibility to pay them equitably. This is easier said than done, of course — in many cases it would require some groups to extensively revise their business model. But choirs regularly manage to pay market prices for instrumentalists, venue rental, advertising, administrative needs, technical needs and other expenses; should they not do the same with the employees whose work defines the very nature of the organization?

At the same time, singers should become more exacting in the two ways that count most for a professional musician: being at an engagement promptly, and being able to execute music accurately and stylishly in the shortest amount of time. Choral musicians often come up dismayingly short in these areas. One cannot demand a professional rate of pay if the service delivered is not up to the best professional standard. And speaking of professional standards, strong choral skills — sight-reading, chiefly — could be much more emphasized in voice training than they are currently, if singers are going to be able to solicit paid chorus work.

Music teachers, universities, colleges and conservatories ought to be very clear about what options and opportunities truly exist for the singers that they graduate every year. Voice students should be learning skills and techniques that will broaden their knowledge base beyond a narrow focus on vocal technique and classical music, to encompass other skills that help them find work in a variety of professional areas.

Grants bodies and unions can raise awareness of this issue, by noting the hourly rate or general compensation parameters of other performers, and by helping to promote and foster the idea of parity for choral singers.

Audience members can raise this issue with arts organizations, grants bodies and governments. Individual and corporate donors can insist that the amount of money given will be dependent on a certain amount of it going directly to singers’ compensation.

More than anything, all parties involved may start talking and sharing information, to begin to come up with their own solutions. Now and then, choral singers have been known to complain about the organizations they work for. For all I know, those who run these organizations are griping about their hired singers as well. Isn’t it time to turn from private complaint to open discussion? It can only help the growth of skill, excellence and artistry within the Canadian choral scene.

If you would like to be part of what I hope will be a creative, good-humoured and energetic discussion, feel free to email me at choralscene@thewholenote.com. All emails will be held in strict confidence. In coming months, look for a choral blog in which open dialogue can take place.

Ben Stein is a Toronto tenor and theorbist. He can be contacted at choralscene@thewholenote.com. Visit his website at benjaminstein.ca.